As Above, So Beneath

Iron, 2016 (Photo: Alberto Lamback)

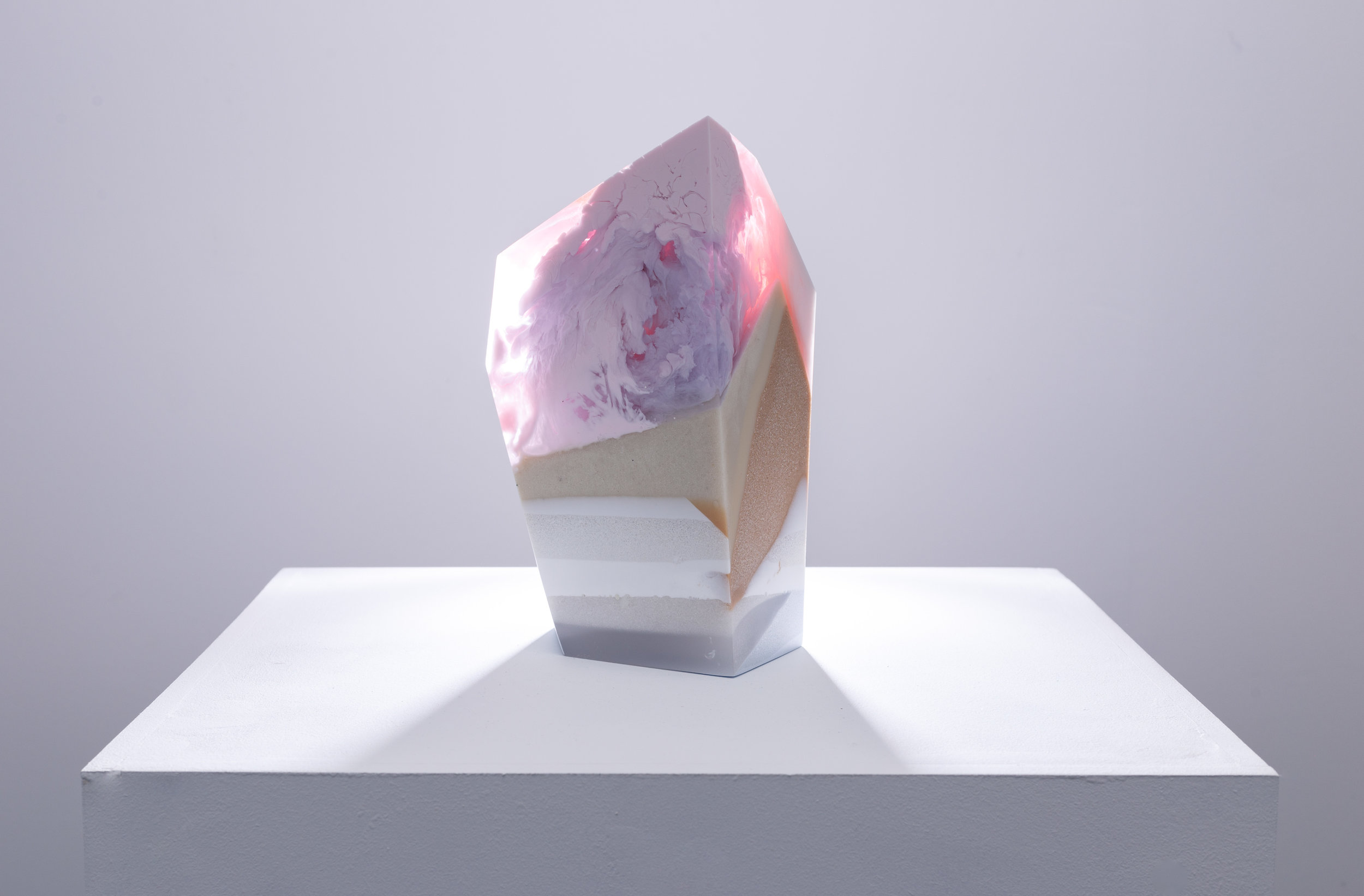

Marble, 2016 (Photo: Alberto Lamback)

Copper, 2016 (Photo: Alberto Lamback)

Salt, 2016 (Photo: Alberto Lamback)

Slate, 2016 (Photo: Alberto Lamback)

Each of the powdered materials in the sculptures is linked to a turning point in societal advancement; to a change in the cultural landscape; to the means by which different civilizations have earthed their own systems of agriculture, manufacture, economy, science and religious practice in the substances of the earth. The sculptures refer specifically to materials caught up in definitive crucial moments of catalysis in human history. The series is comprised of six materials: Copper, Bronze, Iron, Slate, Marble and Salt. All of these are sourced by means of one kind of excavation or another. They are tied to the earth and the excavation of the earth. They epitomize the accumulated layers of minerals that humans have tapped into, enabling bonds of significance between the landscapes of human history and the geology of the earth itself. The way in which the resins are manufactured means they are shaped by a mould, cast and excavated again. As resin shrinks, the artist loosens the layers at a certain decisive point and the work has to be knocked back again, re-shaped, gouged out and unearthed, thus mirroring its natural gemstone or mineral counterparts.

The recurrent focus in making sculpture from resin is the point of catalysis. Everything revolves around the possibilities, which exist in this window of time and opportunity. A genuine exploration of the materials comes about by allowing the natural densities of each material to drop and rise according to innate characteristics and characteristic movements. It is only during the working process that one can discover how these materials might marble—if they are capable of marbling--how they might sink in layers, and how the metals, for instance, might react or oxidize.

Archaeology has made use of the terms, the Stone age, the Bronze age and the Iron age to indicate the physical basis of human progress marked through historical time in tool-making technologies. One of the earliest references to marking time through materials occurs in the poem Work and Days by Hesiod who describes the successive ‘ages of man’ as Gold, Silver, Bronze, Heroic, Iron. History takes shape through developments in agriculture and economy, while the moral dimension to historical change is reflected in the myths of Prometheus and Pandora. Both Ovid and Hesiod describe the same ages (although Ovid omits the Heroic age, to concentrate onthe four material-based ones) and both see the metals and the technological advances connected with them as linked symbolically to the subsequent moral degradation of man and the general deterioration of human society. The myths warn of the temptation and hubris attached to the new found power of technologies.

The title As Above, So Beneath is derived from the so-called Emerald Tablet whose original source is unknown but is thought to be dated as far back as the 6th-8th century. This is a cryptic text that has been understood to contain the secret of Prima Materia (the original matter) and its transmutation. The various formulae hidden in its language are supposed to include the secret knowledge of transitions and transmutations within alchemy and the means of attaining the pure forms of elemental states.

There have been many references to this knowledge in literature and art and a some which are notable have been concerned with Medieval and Renaissance Alchemy. The Emerald Tablet places particular emphasis on the correspondence between Macrocosm and Microcosm, which reflect and parallel one another equally and dually. The microscopic units which comprise the universe correspond to it in structure and are reflected in both physical reality and the metaphysical realm beyond it, in both matter and concept. Macrocosm cannot exist without microcosm, and vice versa.

The title of the show reads As Above So Beneath and the original phrase reads: ‘as above so below,’ which serves to indicate a slight displacement of and alternate inquiry into the original ethos. In sculpture, humanity defines itself by and through materials, pulling what is ‘beneath’ out of the ground to take on form ‘above’. These works amount to an imaginative proposition, a set of imagined archeological artefacts whose potential was buried but has now been disclosed; brought up from below, unearthed and utilized.

Bronze marks the beginning of humanity’s large-scale use of metal and it carries the gravity and prestige associated with the newly established means of tool making. All of a sudden, tools and weapons could be designed and calibrated to achieve the perfect weight, shape and density.

Copper is used generally nowadays for its exceptional thermal and electrical conductive capacities. In medieval hermeticism, copper was regarded as a healing metal and was commonly used to treat influenza, and applied to open wounds either directly or by rubbing copper powder into the forehead twice daily.

Iron was another metal linked crucially to advances in tool manufacture and technology. The earliest worked iron was sourced from meteoric iron and later fine-tuned by means of smelting and removing impurities. Inventions such as iron tipped ploughs enabled the population of Britain to grow substantially while also providing evidence of the international movement of peoples and ideas through the exchange of skill and technique.

Marble allowed sculptors to achieve precision and realism to a degree previously undreamed of and achieved a status as the premier sculptural material. Artists and patrons turned to it as the most convincing medium for bringing life and conviction to religious and mythical themes. The stone’s crystalline structure and material properties mean that light can pass a few millimeters beneath the surface owing to the presence of calcite, while its smoothness and permeability resemble that of human skin, making it an ideal material for the representation of human form and the embodiment of divine and mythical beings.

Slate is formed under circumstances of immense pressure where the material is layered in volumetric planes. Traditionally used as a roofing material owing to its density, durability and plate-like formation, it also was commonly used as a medium for writing from the earliest times until relatively recently. Slate in some ways marks the latest stage in the succession of different ‘ages’ marked by the exploitation of the six materials featured in the show, but it is Salt that binds them all together.

At the edge of the exhibition lies the largest sculpture, made with 3 kilograms of Salt. This piece ties together the show’s various strands exploring historical, mythical and scientific aspects. Here we have a substance with primal value that was regarded as salvific in religious discourse and used as currency in certain economies; 2000 years ago salt had the same value as gold. It enabled food preservation which not only meant survival through the winters but also assisted long distance travel, exploration and ultimately the crusades and land acquisition. In certain religions, we find baptisms in salt water washing away sin. In many mythologies salt water and the sea are foundational to many stories, including Greek and Roman epics, symbolizing a source of good will and preservation, as well as evil intent and destruction, in equal measure.

Traditionally, Salt is sourced in two ways; deep shaft mining and solar evaporation. This encapsulates the idea that the physical manifestation can be captured by means which are both above and beneath us; and the uses of salt tie us physically to the Earth though bodily necessity and metaphysically to the prevention of sin and the averting of Hell. The Sculpture itself encompasses the fundamental qualities of salt preserved in resin. At the point of catalysis, the salt seemed to lie in between the other materials when observing their relative densities. Unlike the other heavier or lighter materials it neither sank immediately nor floated into a stable position. In the finished sculpture, you can see how the material seems to spread slowly through the total volume in clouds of white. The work also includes dark and light colours which evoke its relationship to the themes of a dual existence, above and beneath.

Words by Zuza Mengham 2016